Kircherian Coverpop

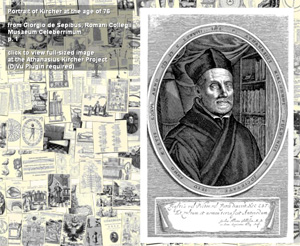

The Jesuit Polymath Athanasius Kircher is a personal hero of mine. I constructed this Kircherian coverpop, which contains a collection of images from his books, which covered such varied subjects as geology, magnetism, architecture, music, egypt, and china. Stanford University Library’s Department of Special Collections has graciously granted me permission to use these images. The coverpop is a quick way to introduce yourself to the astonishing breadth of his interests.

Everyone who is fascinated by Kircher tends to focus on one of his subjects (kind of like picking a favorite Beatle). My favorite Kircher subject is music, which is one of the things he couldn’t possibly “get wrong,” unlike some of his other fields of inquiry in which he made spectacular gaffes, such as his “translations” of the Egyptian Hieroglyphs. In music and art, there is no wrong. There’s just stuff you like, and stuff you don’t like (and what’s not to like about Kircher?). Kircher wrote a couple of remarkable books about music, invented the Aeolian harp, and developed a system for developing counterpoint algorithmically, which was codified in two of his inventions, the Organum Mathematicum, and the Arca Musurgica, both of which were a kind of recipe card index for doing various kinds of useful, and not so useful calculations.

Kircher’s books also feature a number of amazing musical inventions, which are ancestors of our player pianos and our other electronic wonders. Kircher’s books were admired by other baroque composers, including J.S. Bach, who no doubt developed a lot of his techniques from reading Kircher.

Before I was a computer geek, I was a musician. When I first studied species counterpoint — the western system for arranging multiple melodic lines that are played simulataneously — in music school, I had not heard of Kircher. Doing counterpoint homework was a chore, and it occured to me that the rules of counterpoint were so systematic that a computer program could be written which would automate the process. I started trying to write such a program, and this was the beginning of my lifelong fascination with using random numbers to make pretty things. Kircher had the same idea, 400 years ago. I am convinced that if Kircher were alive today, he would be making amazing computer software to do music and art of all kinds.

Surviving examples of Kicher’s Arca Musurgica and Organum Mathematicum (a precursor to the slide rule) still exist, and I would dearly love to create a computer simulation of one in Flash, just so that those of us without access to museum store rooms can manipulate the tablets contained therein, and perform Kircherian calculations anew.

The spirit of Athansius Kircher lives on. He is currently maintaining an excellent blog, The Kircher Society, which is well worth a stop on your daily search for the novel and arcane.

If you’d like to know more about Kircher, who are two good books to start:

Athansius Kircher, The Last Man Who Knew Everthing is a collection of scholarly essays about different facets of Kircher’s fields of interest. The essays come from a 2001 conference on Kircheriana, organized by the editor, Paula Findlen. Sadly, there isn’t enough emphasis on Kircher’s music for my taste, but it’s still one of the better books currently in print.

Joscelyn Godwin’s Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance man and the quest for lost knowledge is a 1979 book which contains a basic overview and some nice fullpage reproductions of many of the illustrations from Kircher’s books.

These books just scratch the surface. For a more in depth introduction, learn some Latin and visit the library at the University of Chicago, Berkeley, or one of the other institutions which has a good collection of Kircher’s books, most of which remain woefully untranslated into English.

If you’re in the Los Angeles area, be sure to visit my favorite place in LA, the Museum of Jurassic Technology, and see David Wilson’s amazing permanent exhibit on Kircher, which contains reconstructions of some of Kircher’s marvelous inventions. He usually has some great Kircher-related stuff in his bookstore too.

March 21st, 2006 at 12:18 am

[…] The traditional call of the cuckooo clock is a two-note melody: “cuc-koo! cuc-koo!” The rendition commonly heard in these clocks is a descending major third (E-C, E-C). The call of the cuckoo was notated as a descending minor third (D-F, D-F) in 1650 by Athanasius Kircher, in his wonderful book Musurgia Universalis. Shown above is an excerpt from a famous illustration in that book which notates the calls of various European birds, including the nightengale and the cuckoo. Perhaps the calls started as minor thirds, but most of the modern clocks I’ve heard use a major third. If you’re unfamiliar with Kircher, check this out. […]